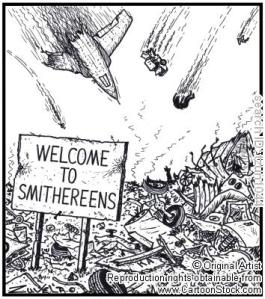

My first encounter with this phrase was in Bugs Bunny cartoons as a kid. It seemed Yosemite Sam was forever hollering, “I’ll blow ya to smithereens!”

My first encounter with this phrase was in Bugs Bunny cartoons as a kid. It seemed Yosemite Sam was forever hollering, “I’ll blow ya to smithereens!”

I had a pretty good idea it meant “blow you to bits” and I was right. “Smithereens” means bits and pieces resulting from a violent action, so to blow something, or heaven forbid someone, to smithereens meant to blow it to pieces.

Where did it come from?

Contrary to my recollections, this term didn’t originate with Chuck Jones or Mel Blanc. It’s actually an Irish word. “Smithereens” is believed to either be derived from or the source of the word “smidirin” which also means small bits or pieces. “Smithereens” has appeared in other forms, such as “smiddereens” and “shivereens” in the 19th century and as can be said of many modern words, it took the passing of time to settle into its present form.

The word first appeared in 1829 in print according to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, however phrasefinder.com found this reference to it a little earlier:

Francis Plowden, in The History of Ireland, 1801, records a threat made against a Mr. Pounden by a group of Orangemen:

“If you don’t be off directly, by the ghost of William, our deliverer, and by the orange we wear, we will break your carriage in smithereens, and hough your cattle and burn your house.”

To say something is “as easy as pie” is to say something is simply or very easily done. Example:

To say something is “as easy as pie” is to say something is simply or very easily done. Example: “The straw that broke the camel’s back” is an

“The straw that broke the camel’s back” is an  “Kick the bucket” is a

“Kick the bucket” is a

“In your face” is a recent American

“In your face” is a recent American  “It’s Raining Cats and Dogs” is an

“It’s Raining Cats and Dogs” is an  “Willy Nilly” is an

“Willy Nilly” is an  “Break the ice” is a common

“Break the ice” is a common  To “beat around the bush” means to refrain from getting to the point. It’s commonly paired with another idiom, “cut to the chase.”

To “beat around the bush” means to refrain from getting to the point. It’s commonly paired with another idiom, “cut to the chase.”